How iNaturalist turns your photos into science

Written by: Henry Hart, Bio-Diversity Ranger

I have an addiction. It isn’t debilitating. In fact, I would consider my interactions with my substance of choice wholly positive. Instead of the temporary high of a coffee, it brings me long-lasting fulfilment and connects me to my place. My addiction is to iNaturalist, the app that records life.

iNaturalist is an app that transforms your cute pictures of weevils, frogs, trees, and encrusting algae into data. Each upload of an organism becomes an ‘observation’. An observation is a record of a single species at an exact time and place.

When you upload a photo, the app will provide an educated guess on what species it might be, using its fancy algorithm. After it has been uploaded, anyone can go onto that observation and suggest a species. An observation will only be confirmed and reach ‘research grade’ when enough people agree on the species. This peer review process is done by the many specialists who use the app. Want to know what insect is latched onto your geraniums and sucking the life from it? There’s probably a perfectly well-adjusted person who sits in front of their computer every evening, refreshing iNaturalist and identifying your observation of an aphid. In this way, iNaturalist is a lot like Wikipedia, which turns out to be a much better source of information than people might think. For every group of life, there is someone with an itching need to identify each species, and another four people who want to argue with them. The result is generally highly accurate data — data that you can use to see which animals and plants live near you. The more the public observes, the finer the detail gets.

Here is the recorded distribution of pīpipi surrounding the Brook Sanctuary on iNaturalist. Pīpipi (brown creepers) are endemic, gregarious brown and grey birds that often noisily flock high in the canopy.

You can see that there are two distinct groups of recordings: one grouping in the forestry at Marsden Valley, and one grouping around Dun Mountain and Wooded Peak. This is a species that used to be common right down to coastal Nelson but has become restricted to the low-predator-density forestry and upland forests. There are, however, two outlier observations — one right down by Brook Street and one inside the Sanctuary on Falcon Spur. This can be explained by the behaviour of the species. This species forms transient flocks that include many creepers and are sometimes mixed with species like kākāriki. They have not yet established themselves in the Sanctuary, probably due to sheer bad luck. Hopefully, over time, we may observe a takeover. Better yet, if aerially dropped 1080 (a biodegradable toxin used for predator control) was used outside the Sanctuary, the outside creeper populations would produce more offspring that would be more likely to disperse into the Sanctuary. This is a species that would otherwise be impossible to reintroduce. All of this information could be gleaned from sitting at my computer. The only thing that was needed was the observations (several of which are mine).

Additional data can be gleaned from your images too.

Is my giraffe weevil a boy or a girl? What time of year does this tree flower? What is the host plant for this mistletoe in this area? What plants does this fungus associate with? All of this data is why iNaturalist is a great citizen science tool. This information is available to see at the click of a button, free for scientists and laypeople to educate themselves and others. It can record declines, expansions, invasions, and finer definitions in the recorded distributions of life on Earth.

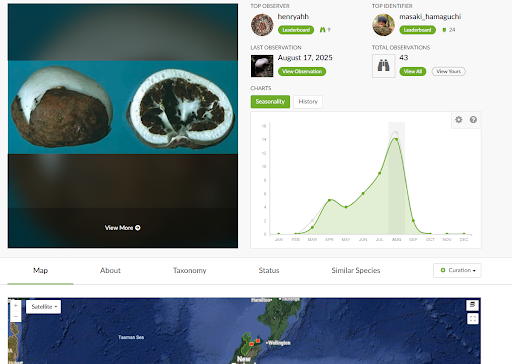

Here is the page for the Fischer’s egg fungus, a critically threatened species that is common at the Sanctuary. You can see when it is most often observed, its distribution, its taxonomy and threat status, as well as the Wikipedia article associated with the species. Each time you add a new observation, others can use that distributional, phenological (timing), and other metadata to expand the knowledge of how and where this organism lives. More and more recently, iNaturalist data is being used in scientific papers and revisions of species’ threat statuses.

But I’m not a scientist; I’m a person. I use iNaturalist to learn.

It’s great for learning scientific names. Scientific binomial names are more helpful than you would think. Each organism has two italicised Latin names, Genus species. A genus is a group of organisms that are all more closely related to one another than to other members of their family. A species denotes a specific group of organisms that are more closely related to one another than to other members of their genus. Learning what plants or animals are in the same genus or family forces you to look at common characters. Organisms in the same family will share characteristics that are unique to that family. Understanding this and pairing it with your observations is a doorway into the wonderful world of evolution and biogeography.

Scientific names transcend the failures of common names, which mislead you as to what an organism is related to. The colonial English famously named any coniferous tree a pine, despite pines being native to the northern hemisphere. Or where a common name is used for many unrelated species, like the te reo Māori name ‘mikimiki’ being used for dozens of unrelated species of small-leaved shrubs. That’s not to say that Māori names are unimportant, and as Kiwis, we ought to use te reo Māori names as much as possible. Luckily, these names are also recorded on iNaturalist!

iNaturalist gamifies the whole experience of learning. It gives you a dopamine hit every time you find something new, hence its addictive qualities. Like Pokémon Go, the app that encouraged people to get outside and catch fake animals and stuff them into tiny balls to fight other fake animals, iNaturalist encourages you to collect photos of real-life animals without getting run down in the street. When you learn which species are which, you begin to notice where they grow and what plants and soils they associate with — and at that point, you’ve just learned forest ecology.

Rare observations

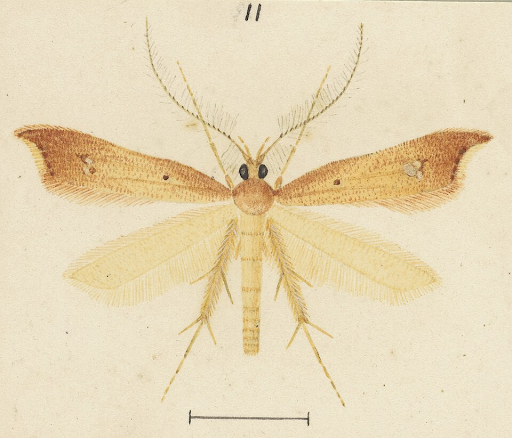

Observations are just formalising what you see every day anyway — except they force you to look closer. When you do, you might just find something rare. Last autumn, Chelsea, Shaeleigh, and I went out catching moths one night. We caught a couple of small brown moths. They didn’t seem special, though they were still beautiful. It turned out that they were a very uncommon species that hadn’t been recorded on the South Island for 100 years. Its name: Thambotrica vates, ‘wonder-haired prophet’. (Entomologists often give rare moths eccentric names to encourage eccentric people to go look for them.) The Sanctuary has now become one of a dozen known sites for this species. It shows that just because something may look common does not make it so. Small, cryptic animals like this often suffer from a lack of exposure. They could be more common than they seem because people don’t pay them any mind. If we rely on a handful of lepidopterists to record the country’s highly endemic moths across the whole country, we won’t get a lot of data. We know a lot less about our floral and faunal distributions than one might think. And that is why you should help!

Driven by the community, we can improve our collective knowledge, connect to the wild places in which we belong, and get addicted to a substance that is good for you!